Any SAT-word loving geek can break down the word neurogastronomy. Neuro indicates brain and gastronomy links to food and culinary. There is a lot of interest in brain health and nutrition these days, looking at how our brain lights up when we eat certain things or the communication we get from our gut or how nutrients like choline can impact brain health. But none of these seems to fit into neurogastronomy specifically. So what is it?

I set out to find the answer this weekend at the Third Annual Conference of the International Society of Neurogastromy in Lexington, Kentucky on the campus of the beautiful University of Kentucky. As we often engage with diverse stakeholders, I am used to meeting people from a variety of disciplines but I have literally NEVER encountered such a group of diverse individuals – from health professionals such as neurologists, general practitioners and dietitians, to academics working in sociology, philosophy, psychology, food science and sensory science, to foodies such as world-renown chefs, culinary historians and master bourbon distillers (we were in Kentucky afterall). Oh yeah, and then there was the guy building the internet of food.

But we all gathered with the purpose, as set out by the ISN, of finding ways to improve public health through better understanding how our brains impact what, how, when and how much we eat. There were some great “Did You Know?”s coming out of the symposium. For example:

- Did you know that while the area of the human brain that senses smell (the olfactory bulb) is smaller in humans than dogs, we have a similar amount of neurons and they can interpret the information in a much more sophisticated way? (John McGann, PhD, Rutgers University)

- Human’s metabolic signals could be contributing information to our brains when we go to make decisions about food….especially when that food contains yummy elements like fat and carbs. (Dana Small, PhD, Yale University)

- The “health halo” around foods labeled organic or billed as healthy alternatives not only make us eat larger portions of those foods, they could make us more judgmental of others or less likely to be willing to volunteer our time. (Rachel Herz, PhD, Brown University)

- For the 30-40% of patients with epilepsy who don’t respond to pharmaceutical treatments, the ketogenic diet can all but erase symptoms (Dr John Rho, University of Calgary)

- Similar to the flavor wheels used in the wine and spirits industry, creating a flavor wheel of vegetables can increase acceptance and diversify palates of non-veggie eaters. (Amanda Archibald, RDN, The Genomic Kitchen)

We have clearly not solved the obesity problem by looking only at how food impacts us from the neck down. Integrating the brain into the equation is an important next step to improving public health and I look forward to continuing the journey with the ISN.

Related News

January 25, 2021

Eat Well Connect Voices: Tessa Nguyen

In this latest installment of our Eat Well Connect Voices Q&A, Tessa Nguyen, RD, LDN, of Taste Nutrition Consulting shared her thoughts on what…

November 27, 2020

The Conference Discussing the Future of Food, Drink and Nutrition Goes Virtual

This October, Food Matters Live held its first virtual conference. The conference focused on identifying opportunities in a changing consumer-driven…

November 19, 2020

Partner Highlights: Global Alliance for Improved Nutrition

In the global fight against hunger and malnutrition, few organizations are as impactful as the Global Alliance for Improved Nutrition (GAIN). Since…

November 18, 2020

Eat Well Connect Voices: EatWell Exchange

In this latest Eat Well Connect Voices Q&A, Ashley Carter, RD, LDN and Jasmine Westbrooks, MS, RD, LDN of EatWell Exchange Inc. share their…

October 12, 2020

Next Normal: Optimal Nutrition for a Pandemic Reality

The COVID-19 pandemic has had a profound impact on us all, and the food, nutrition and healthcare industries are no exception. While nutrition…

October 1, 2020

Maintaining Sustainability Commitments While Protecting Profits

Earlier this month, I had the opportunity to present at the 2020 Vitafoods Europe Virtual Expo and discuss how consumer packaged goods companies can…

September 20, 2020

Eat Well Connect Voices: Shahzadi Devje, RD

We're thrilled to connect with Eat Well Connect (EWC) member Shahzadi Devje, RD as she shares her thoughts on using nutrition communication as a tool…

August 20, 2020

We’re hiring an intern for the fall 2020 semester. Apply to join our team!

We’re looking to hire a graduate student for an internship this fall. Our ideal candidate is a current master’s student in nutrition, dietetics or a…

July 29, 2020

We’re hiring a contract/temporary Account Coordinator. Apply to join our team!

We’re looking to hire a Contract/Temporary Account Coordinator to cover for one of our team members. Our ideal candidate is a registered dietitian…

July 16, 2020

We’re looking for a Virtual Events Coordinator! Apply today!

Join our game-changing team as an experienced Contract Virtual Event Coordinator to help us manage virtual events on behalf of our food and nutrition…

June 29, 2020

Nutrition Communication in the Time of COVID

According to a recent survey conducted by the International Food Information Council (IFIC), consumers consider health professionals and registered…

June 4, 2020

Impactful Communication: Meaningful Messages to Inspire Change

Do you want to be more impactful in your work as a dietitian or nutrition professional? Learning to effectively build a message and communicate it to…

May 21, 2020

Register: Healthy Food Promotion

The best way to prevent illness is to avoid being exposed to the COVID-19 virus. Practicing social distancing and proper hand washing can help…

May 21, 2020

Register: Food and Nutrition Standards

Warning labels and restrictions on what can be purchased with federal dollars have long been held up by some as solutions to inform consumers with…

May 21, 2020

Register: Hunger, Inequality and Nutritious Food

In light of COVID-19-related job losses, food banks and federal assistance programs are playing a central role in addressing the growing needs of…

May 19, 2020

Putting Nutrition to Work: Acting on Our Vision that Good Nutrition is Good Business

Workforce nutrition programs offer benefits for employees as well as businesses, such as reduced absenteeism, increased productivity and improved…

September 18, 2019

Exploring the Ongoing Evolution of Food, Sustainability and Nutrition at The Future of Food Summit

As Eat Well Global further establishes its unique position empowering global change agents in our field, we actively seek more perspectives and…

August 7, 2019

Climate, Culture & Economics: Expanding our Nutrition Perspective at the Asian Congress of Nutrition

Hosted by the Federation of Asian Nutrition Societies (FANS) every four years, the Asian Congress of Nutrition is Asia’s prime convening of food and…

July 16, 2019

“No one is your enemy” and other things I learned in Geneva last week

Last week I joined nearly 30 public and private sector leaders from all over the world as the inaugural cohort of a very special course, Together for…

June 23, 2019

Marrying Medicine and Nutrition: Health Meets Food Conference

Hosted by the Tulane University School of Medicine, Health Meets Food’s 6th annual Culinary Medicine conference brought together primarily physicians…

April 25, 2019

The Power of Pairing, Partnerships and Produce at PBH Consumer Connection Summit

Launching a fresh new campaign, “Have a Plant”, PBH connected consumers’ increasing interest with adding more plants to their diet to their ongoing…

April 15, 2019

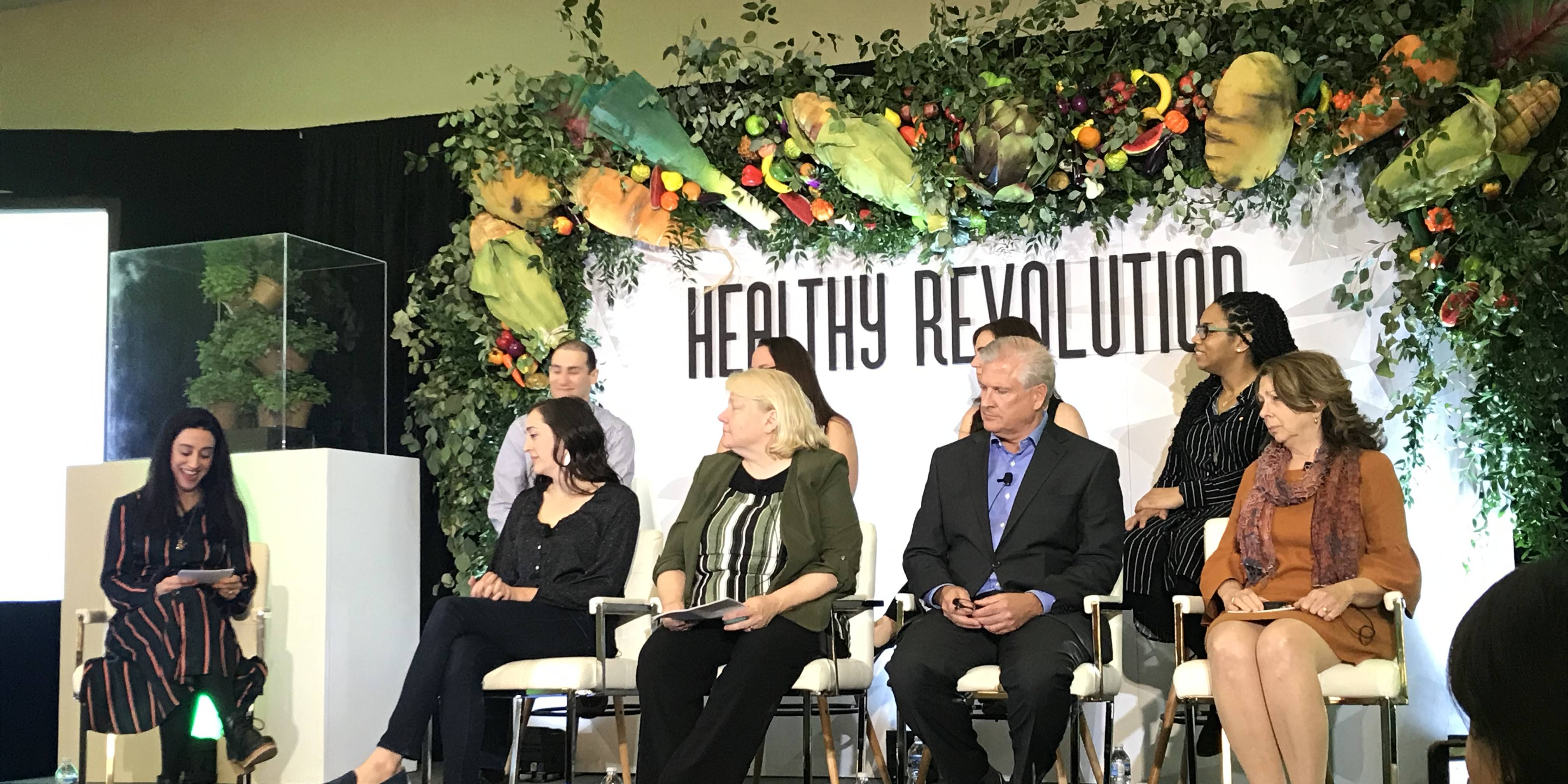

Accelerating Healthier Futures Together

Over the years, we’ve seen Partnership for a Healthier America (PHA) embark on new initiatives, bringing along their star-studded friends to amplify…

April 8, 2019

The 2nd Annual Culinary Nutrition Conference

Chefs and nutrition professionals came together for the 2nd Annual Culinary Nutrition Conference this month at the Institute of Culinary Education…

April 3, 2019

Internet of Food Brought to Life at IC-Foods 2019

When the concept of the “Internet of Food” comes up, people often ask, “don’t we already have an internet? And can’t you find food there?” The…

March 22, 2019

The Chicago Council on Global Affairs: Global Food Security Symposium 2019

For the past 10 years, The Chicago Council on Global Affairs has been convening key stakeholders from the public, private and NGO sectors at their…

February 28, 2019

The Evolving Regulatory and Marketing Landscape of Lab-Grown Meat

Cell-cultured meat, also known as lab-grown meat or clean meat, is generated through a complex process using cells from healthy animals and combining…

December 20, 2018

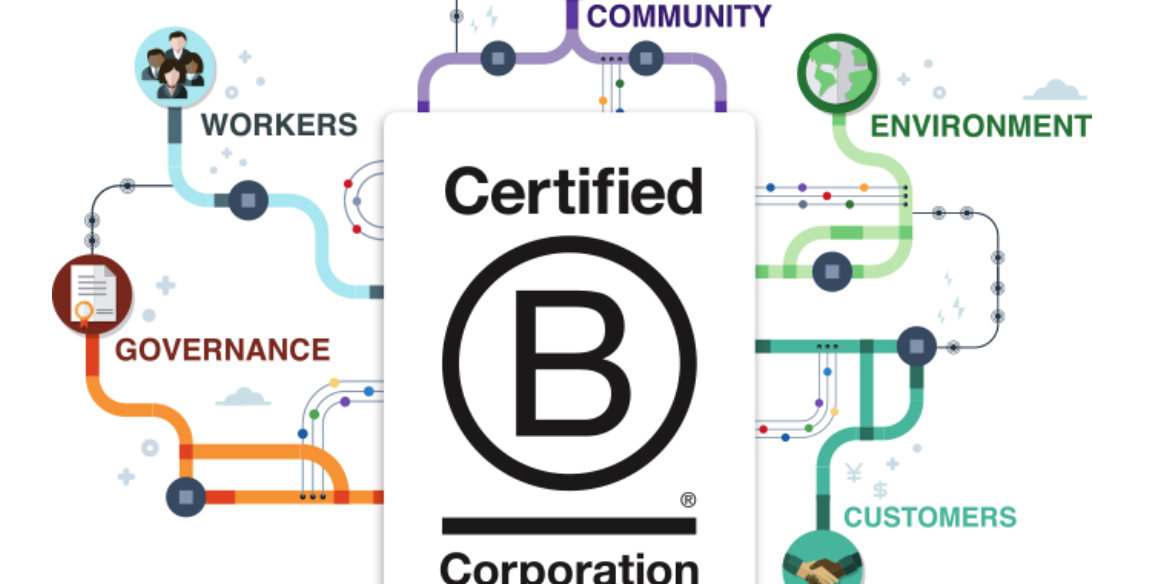

Eat Well Global Proudly Announces B Corp Certification

We are excited to announce Eat Well Global is now officially B CorpTM certified!

December 12, 2018

PRESS RELEASE: Eat Well Global Joins Corporate Leaders in Social Responsibility with Recent B Corporation® Certification

Certified B Corporations® include businesses that voluntarily meet the highest standards of social and environmental performance, public…

November 7, 2018

PRESS RELEASE: Healthy Marketing Team and Eat Well Global join forces to help industry address rapidly changing consumer nutrition market in North America

The international brand strategy and nutrition innovation agency, Healthy Marketing Team (HMT), announce their cooperation with Eat Well Global, Inc…

October 25, 2018

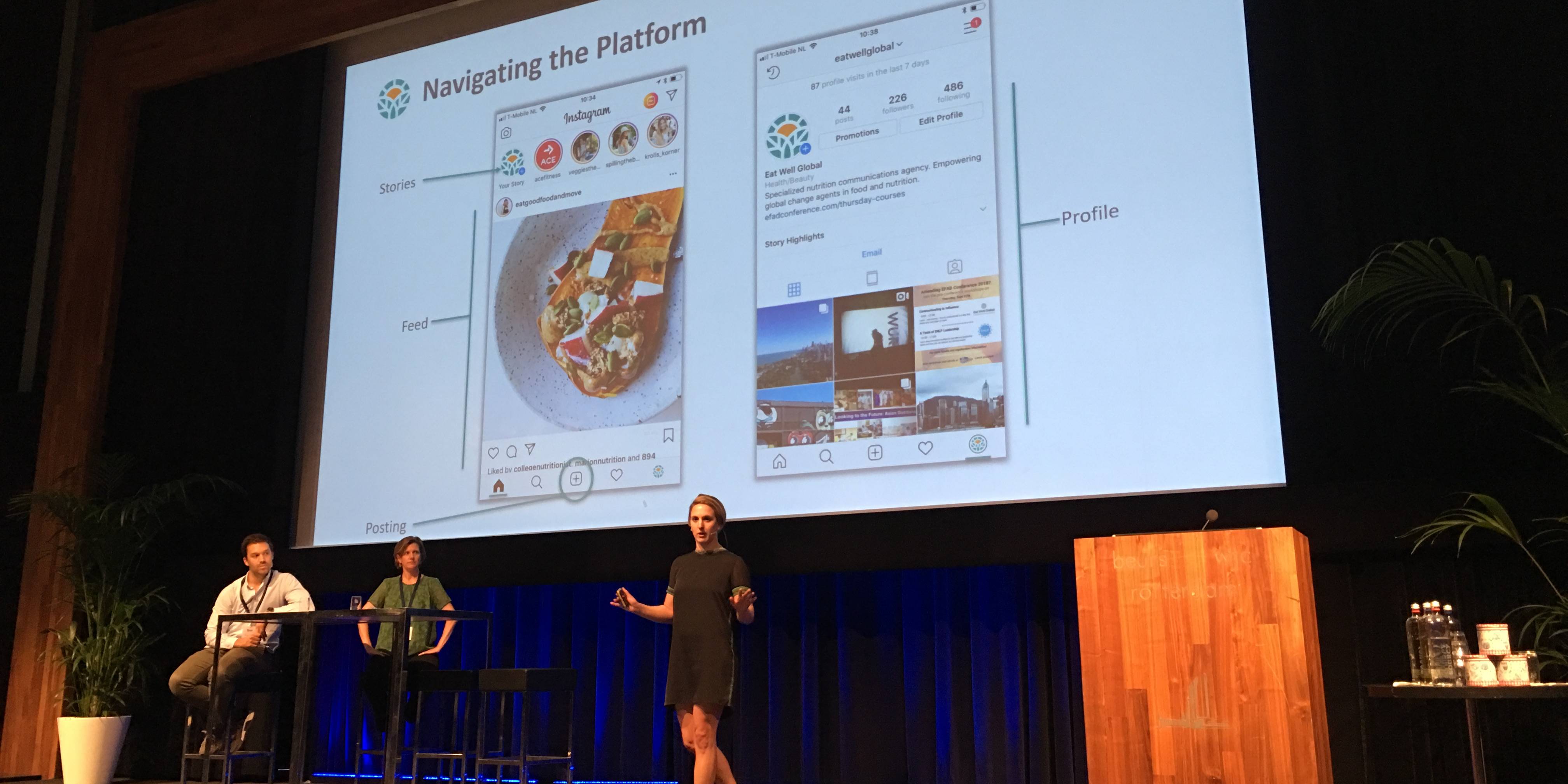

Eat Well Global Brings Nutrition Communication to the Forefront at EFAD 2018

Eat Well Global participated in the 40th Anniversary European Federation of the Associations of Dietitians conference in Rotterdam, the Netherlands.…

September 6, 2018

“Nutrition is Everyone’s Business”: Insights from the SDG Conference – Partnerships are Critical to Ending Hunger

This August, Eat Well Global attended the SDG-Conference ‘Towards Zero Hunger: Partnerships for Impact’ at Wageningen University & Research in the…

August 20, 2018

Communicating to Influence at EFAD Conference 2018

For dietitians, the ability to communicate effectively is an essential skill. Whether working in a hospital, school, food company or even your own…

May 11, 2018

Partnership for a Healthier America Summit Brings 360 Degree View of Better Health

The 2018 PHA Summit brought together diverse stakeholders to support their mission: make the healthy choice, the easy choice.

March 14, 2018

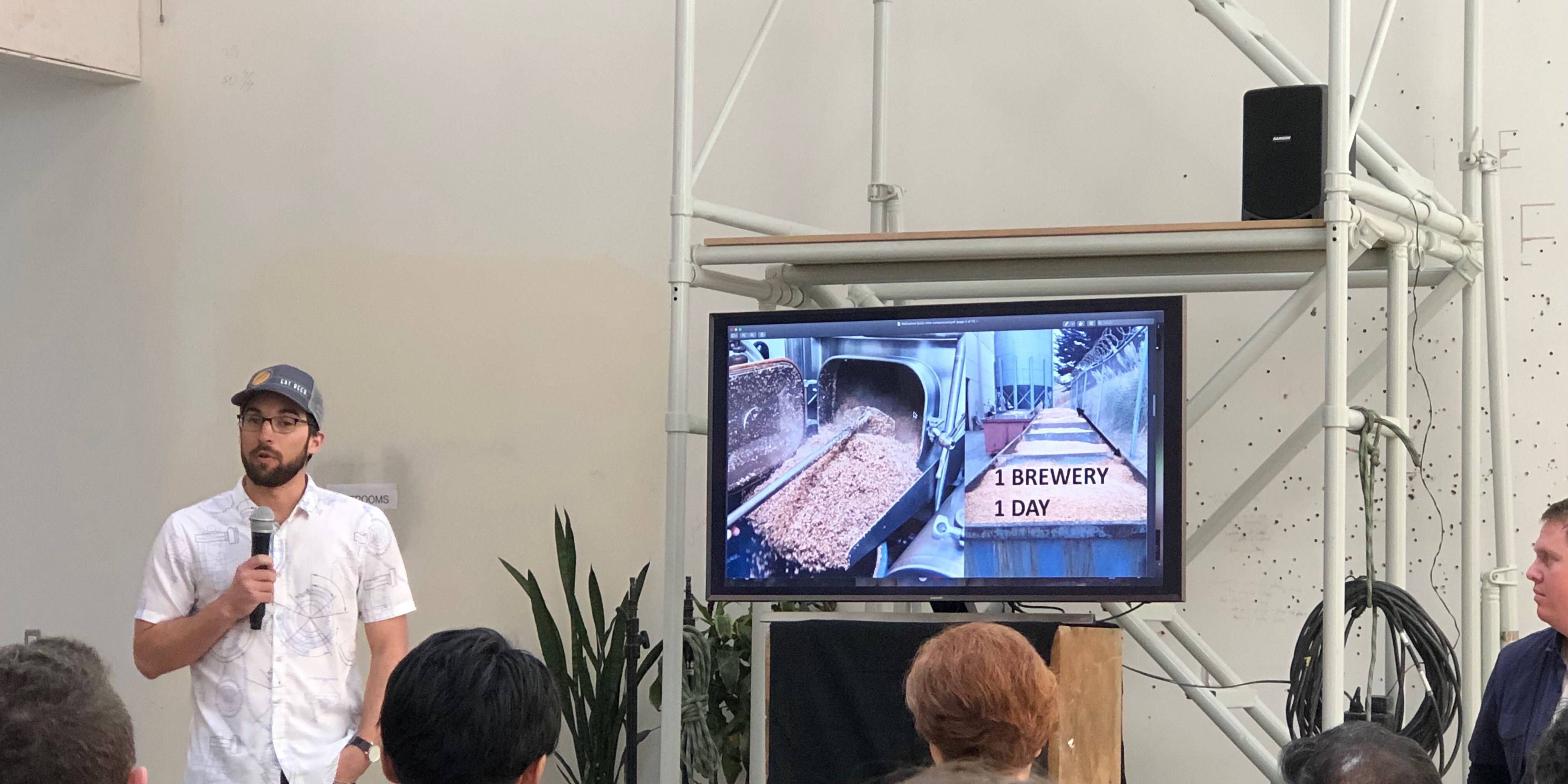

Food Tank 2018 Highlights Need for Farmer Support

At the recent Food Tank Summit in Washington, D.C., farmers, senators, members of Congress, nonprofit and business leaders, media, and young…

November 22, 2017

Dubai International Food Safety Conference Brings Big Data to the Plate

Technology and food safety were the name of the game at the 11th Annual Dubai International Food Safety Conference, which took place November 19-21,…

June 15, 2017

Harvesting Insights from the Next Generation of Food Security Innovators: Thought For Food Global Summit 2017

Have you ever heard of choco-panda ice cream? Me neither. How about a superhero on a mission to teach kids about nutrition and food security? If…

May 16, 2017

Flexible & Entrepreneur Dietitians – Global Dietitians interviews Eat Well Global

Global Dietitians interviews Eat Well Global's founding partner Julie Meyer

May 9, 2017

Eat Well Global on Influencer Trust at Food Vision Asia

It is no news: achieving a healthy lifestyle is top of mind for millions of people around the globe and social media plays a big role in driving…

March 17, 2017

Eat Well Global Talks Authenticity in Food Navigator Interview

With an apparent rise in distrust of science and facts coupled with an increase in social media marketing, there has been a shift in consumer…

March 14, 2017

Eat Well Global at Food Vision in London!

Trend makers, marketing and communication specialists and industry leaders gathered at the Food Vision event in London, from 1-3 March. Among the…

January 26, 2017

Eat Well Global addresses health influencers & brand power in Food Navigator article

In times where consumer demand for transparency and authenticity intersect with fast pace influencer marketing, reaching consumers through trusted…

January 17, 2017

Eat Well Global talks 2017 global food trends on Food Navigator-USA’s Podcast

To kick off 2017, Julie Meyer, co-founder of Eat Well Global and GA4HNC, participated in two episodes of Food Navigator-USA's Soup-to-Nuts-Podcast.

January 2, 2017

Convenient, Committed and Cool: 2016 NY Produce Show Review

Today's consumer seeks more from their produce and industry is delivering

December 20, 2016

The American Public’s Opinion on Food Science

A recent survey by the Pew Research Center asked Americans about their opinions regarding the science behind food and health recommendations and…

December 12, 2016

What Americans Think About Healthy Eating

With impending changes in the political climate, many people have been asking what this means for the future of food policy.

November 22, 2016

Food Vision USA: Innovation, Disruption and What’s Next

Leaders from start-ups to trend makers to innovative disruptors share their thoughts on the big question: what's next?

November 14, 2016

Want people to eat more fruits and vegetables? Inspire them.

As a nutritionist, I love this statement. As a communicator, I couldn’t agree more.

October 5, 2016

ICD 2016: How Dietitians Can Impact Sustainable Eating

What role can (and should) dietitians play in the sustainability dialogue? We went to Granada to find out!

August 17, 2016

The Future Is Now: New Harvest 2016

Several hundred (309 to be specific) researchers, entrepreneurs, visionaries, futurists and interested parties gathered under sunny skies in San…